Part IV. Die Errors:

Die Breaks:

Cuds

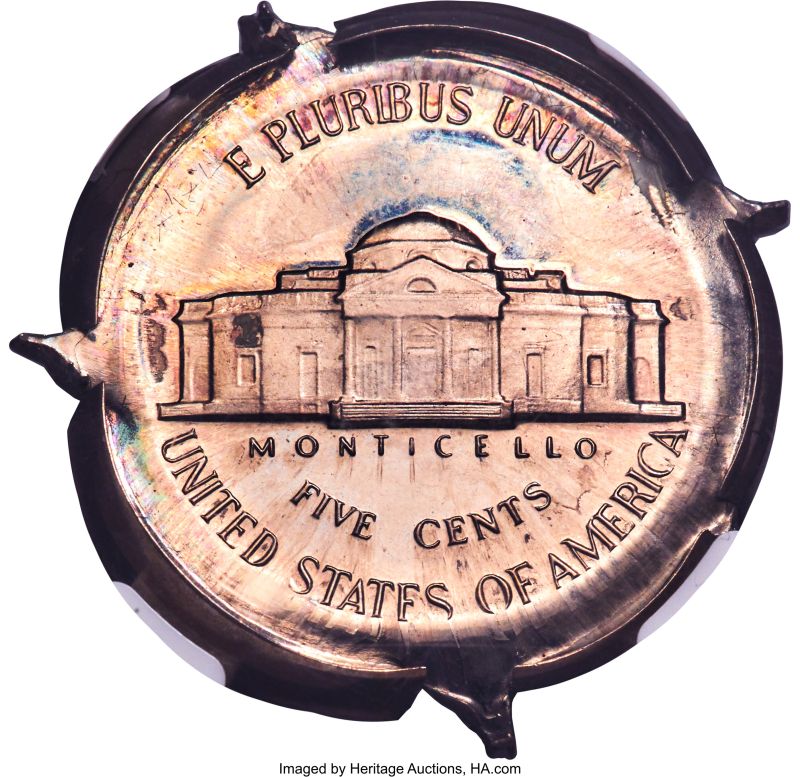

Definition: A cud is a die break that involves the rim and at least a little bit of the adjacent field or design. The vast majority of sizable die breaks are cuds. Cuds can assume a wide variety of shapes including ovoid, crescentic, and irregular. Most cuds represent spontaneous brittle failure. A small minority arise as the result of impacts.

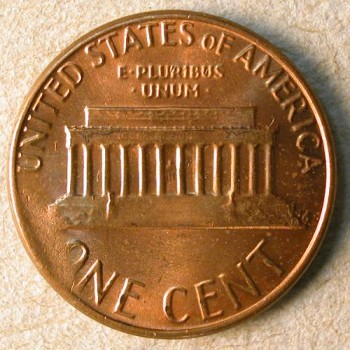

A large cud is seen on the reverse face of this 1988 cent. The obverse face shows a featureless pucker where coin metal withdrew from the obverse die and bulged into the void in the reverse die face.

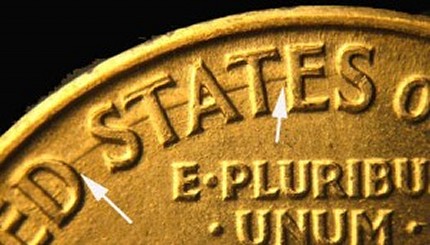

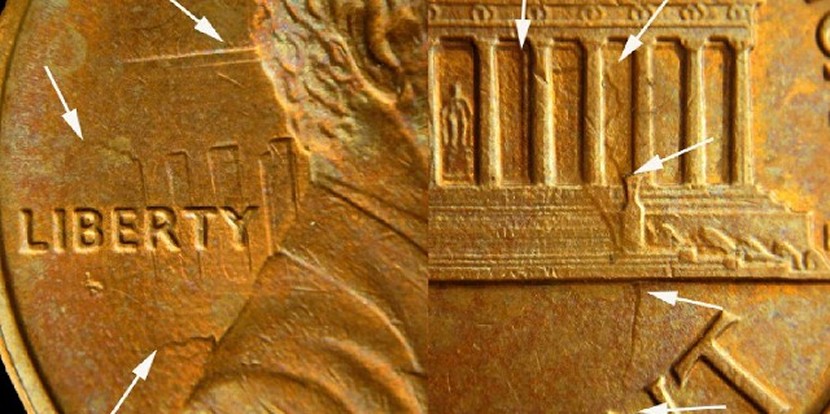

Many cuds maintain a consistent size and shape through a production run. Some cuds grow larger through a production run as additional pieces of die steel break off.

Shown above is a three-stage cud progression in a 1982 cent. In Stage 1, the cud is ovoid. In subsequent stages the cud grows larger and more irregular.

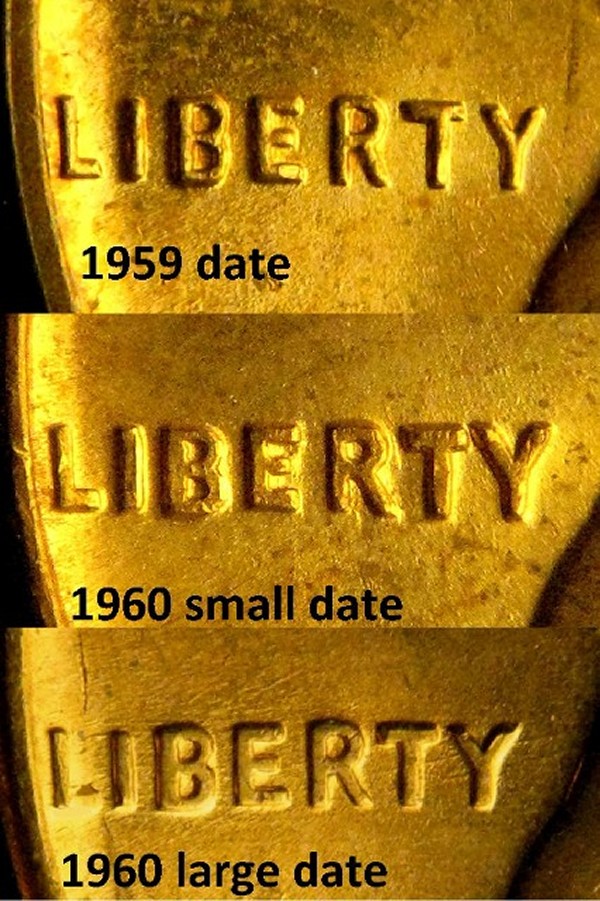

Shown above is a three-stage cud progression on the reverse (1062 Flud) of an 1863 Broas Pie Baker store card token from the Civil War era.