|

2011-12-26

2012 01 16

MD-4Outlying half-ring points to pre-plating damage to 1-cent planchet

MD-5

2012 03 19‘Two-tailed’ Canadian cents: mules or pseudo-mules?By Mike Diamond-Special to Coin World |

|

|

MD-11

|

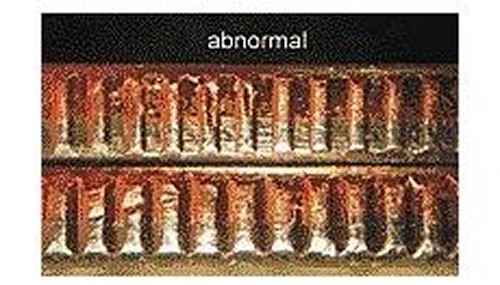

A second case of abnormal reeding on a State quarter dollar By Mike Diamond-Special Article first published in 2012-04-16, Expert Advice section of Coin World

A side-by-side comparison of two 2008-P New Images by Mike Diamond.

|

|

|

A wise old aphorism from the realm of science declares that “fortune favors the prepared mind.” Marilyn Keeney’s mind was certainly prepared when she stumbled across a second example of abnormal reeding in a State quarter dollar. The first example — also discovered by Keeney — was reported in the Jan. 25, 2010, Collectors’ Clearinghouse. Back then she encountered a group of 2008-P New Mexico quarter dollars struck within a single damaged collar. As shown in the accompanying photo, the reeds (vertical ridges) on the edge of each affected coin are unusually low and narrow and are separated from each other by abnormally wide, flat valleys. This appearance reflects damage to the sharp tips of the corresponding ridges on the working face of the collar. The apex of each ridge was removed by abrasion or machining. Horizontal scratches in the valley floors seem to point to the use of some kind of rotating, cylindrical device. The original discussion also included a much earlier case involving a 1964-D Washington quarter dollar. That example showed a similar, but somewhat less uniform pattern of low, narrow reeds and broad, flat valleys. The same sort of collar damage has now been found on the edge of some 2007-P Wyoming quarter dollars. Here the damage is not nearly as severe as that seen in the earlier examples. The damage also affects only about half the edge. The edge exhibits a gradual transition from normal reeding to abnormal reeding, with the widest valleys seen at around 8:00 (obverse clock position). At least three die pairs are represented within a group of five quarter dollars that were found by Keeney. This is not particularly surprising, as the same collar is often used through several die changes. Keeney’s two finds leave little doubt that many other cases of similar damage are yet to be discovered. In fact, I stumbled across another example while rummaging through my modest collection of coins with odd-looking reeding. This time the collar damage was detected on a 1967 quarter dollar that combines a tilted partial collar with an uncentered broadstrike. In other words, the collar was strongly tilted and a portion of it was positioned beneath the plane of the anvil (reverse) die face. The reeds are low, narrow and widely spaced (see photos). A particularly interesting feature is seen at 2:30. Here the reeds taper strongly as they approach the top of the collar. The same phenomenon is seen on the 1964-D Washington quarter dollar. This provides a clue as to the likely cause of the damage in all these examples. In many collars the entrance is beveled. Judging from a large sample of partial collar errors, the length of this beveled transition zone between the top of the collar and its working face is highly variable. A sloping entrance deflects the impact of a misaligned hammer die, helping to prevent damage to both the die and the working face of the collar. It also probably makes for more reliable insertion of the planchet. In either case, the damage would be expected to occur most frequently, and achieve its greatest severity, along the upper portion of the collar’s working face. This neatly explains why the reeds sometimes taper toward the obverse face and the top of the collar. Coin

|

|

http://www.coinworld.com/articles/a-second-case-of-abnormal-reeding-on-a-state-/ Copyright |

2012 04 30

Second cupped, two-tailed Canadian cent surfaces

By Mike Diamond-Special to Coin World | April 14, 2012 9:58 a.m.

Article first published in 2012-04-30, Expert Advice section of Coin World

This deeply cupped 1968 Canadian cent carries the reverse design on each face. It is almost certainly a double-struck pseudo-mule.

Images by Mike Diamond.

In the March 19 Collectors’ Clearinghouse column, I reported on a deeply cupped 1978 Canadian cent allegedly struck by two reverse dies. Considered unique at the time, it now has a companion.

After my column came out, I was contacted by Jeff Chapman who sent me photos of a nearly identical example that was struck in 1968. The presence of this second specimen further undermines the idea that either cent represents a two-tailed mule. Chapman’s cent is almost certainly a pseudo-mule that was produced under one of three scenarios described in my earlier column.

1. A cent is struck normally, flips over, and lands on top of another planchet, with the Maple Leaf design facing the planchet. A second strike flattens the original maple leaf design but does not erase it, while the hammer die obliterates the queen’s bust and simultaneously imparts the second Maple Leaf design.

2. Two planchets are struck together within the collar, creating two in-collar uniface strikes. The top coin flips over and comes to rest on the same blank surface or on top of a fresh planchet. The next strike flattens the original Maple Leaf design, while the original featureless surface is struck by the hammer die, which imparts the second Maple Leaf design.

3. A cent sporting an in-collar first-strike brockage of the Maple Leaf design on its bottom face flips over and comes to rest on the anvil die. Another planchet is inserted on top of the brockaged coin and is struck into it. The bottom face of that newly-struck coin carries a first-strike counterbrockage of the Maple Leaf design.

The second scenario would seem to be the most likely explanation for both the 1968 and 1978 cents.

Interestingly, when the 1968 cent was encapsulated by Professional Coin Grading Service, it was provided with a diagnosis entirely different from the 1978 cent. Instead of claiming it was a “die cap struck by two reverse dies,” PCGS described it as an “obverse die cap with reverse counterbrockage.”

It seems PCGS may have entertained a pseudo-mule hypothesis of its own, similar to the third scenario. It’s hard to say for sure, as the description is rather muddled. Chapman’s coin obviously cannot be an obverse die cap, since it is the reverse design that decorates the inside of the cup. Perhaps PCGS meant to call it a reverse die cap. Maybe the grading service was confused in thinking that the Maple Leaf design is on the obverse face. Or perhaps PCGS conflated the hammer die with the obverse die for the cent.

Identifying it as a die cap is easier to understand, but even this claim can be disputed. Effective striking pressure is greatly increased when two discs are stacked on top of each other. If both discs are struck out-of-collar, the top coin will curl up to surround the neck of the hammer die (see the Dec. 7, 2009, Collectors’ Clearinghouse). Only one strike is needed to form an impressive cup.

While the third scenario requires only one strike, scenarios 1 and 2 require two. But since the coin has to flip over between strikes, we still can’t consider the resulting coin a die cap. By definition, a die cap has to be affixed to the same die face through both strikes.

It seems unlikely that the flattened Maple Leaf design on either cent is a flipover, first-strike counterbrockage. Even under carefully managed conditions, the peripheral portions of any first-strike counterbrockage should be closer to the coin’s edge, and might even run off the edge of the coin.

While I haven’t encountered any cupped pseudo-mules among U.S. coins, I have seen coins that were almost certainly struck by them.

Shown here is a Lincoln cent with a perfectly centered, mid-stage flipover brockage of the obverse design on the obverse face. Struck in-collar, it was generated by a “two-headed” pseudo-mule most likely produced under the first scenario. In this case the pseudo-mule definitely became a die cap.

The next specimen is a massively expanded, broadstruck 5-cent coin with an almost perfectly centered flipover brockage of the obverse design on the obverse face. Although faint, the incuse design is complete, establishing it as a first-strike brockage. The strike that generated the brockage also undoubtedly converted the overlying 5-cent coin into a two-headed pseudo-mule (scenario No. 1).

Coin World’s Collectors’ Clearinghouse department does not accept coins or other items for examination without prior permission from News Editor William T. Gibbs. Materials sent to Clearinghouse without prior permission will be returned unexamined. Please address all Clearinghouse inquiries to cweditor@coinworld.com or to 800-673-8311, Ext. 172.

http://www.coinworld.com/articles/second-cupped-two-tailed-canadian-cent-surfac/

Copyright 2012 by Amos Hobby Publishing Inc. Reposted by permission from the March 22, 2012, issue of Coin World.)

2008p Liberty Silver Bullion With 2007 Reverse

Part III. Die Installation Errors:

Transitional Reverse (Minor Temporal Mismatch):

2008-P Silver Eagle with 2007-P Reverse

Definition: Subtle differences in design details can differentiate dies used in different years. Whether accidental or purposeful, obverse dies are sometimes mated with a reverse die meant for a previous or subsequent year. These are often called “transitional reverses”. Well-known examples include 1992(P) and 1992-D Lincoln cent obverses mated to a 1993 reverse.

The U.S. Mint normally takes a bit more care when they are producing proof and bullion coins. The One Dollar Silver Eagle bullion coin had a relatively mistake-free history until 2008. In that year, one or more 2008 silver eagle obverse dies were mated with a 2007 reverse die.

The most obvious difference between the two dies is found in the style of the U of UNITED.

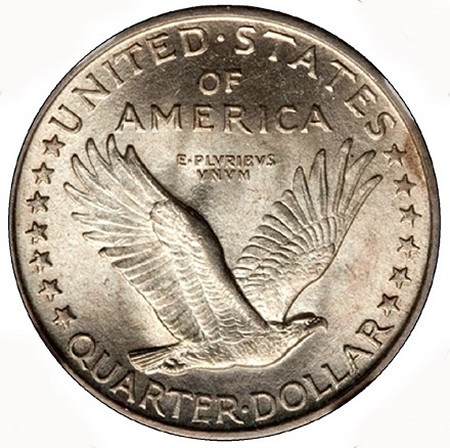

1917 Standing Liberty Quarter

PART I. Die Subtypes:

Mid-year Design Modifications:

1917 Standing Liberty Quarter; Type I and Type II

Definition:The below images show the Type I and Type II Standing Liberty Quarter. Both the obverse and reverse of this coin underwent extensive modifications in the year 1917. One noteworthy change was the covering of Liberty’s exposed right breast with chain mail (see image below of the Type II quarter). Urban legend claims that the exposed breast was seen as indecent and created a public outcry. This forced the U. S. Mint to produce a more modest allegorical figure of Liberty.

A different explanation can be found on Wikipedia

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standing_Liberty_quarter).

“Roger W. Burdette suggests that this change was not unusual for MacNeil (original designer of the Standing Liberty Quarter), who was increasingly cladding female figures in garments which covered their breasts, as with his statue Intellectual Development, sculpted around that time, and also reflected the deterioration of the international situation in February 1917, as the United States moved towards war with Germany.

The redesign of the obverse has led to an enduring myth that the breast was covered up out of prudishness, or in response to public outcry. Breen states that “through their Society for the Suppression of Vice, the guardians of prudery at once began exerting political pressure on the Treasury Department to revoke authorization for these ‘immoral’ coins”. Ron Guth and Jeff Garrett, in their book on US coins by type, aver that the covering up of Liberty was “a change never authorized by MacNeil”. Numismatic historian David Lange concedes that there is no evidence of outcry from the public, but suggests that the decision to change the coin was “more likely prompted by objections from the Treasury Department.”

On July 9th, 1917 a bill was enacted by Congress authorizing the changes to the Standing Liberty quarter.

TYPE I

In comparing both the obverse and reverse of both types of 1917 Standing Liberty quarters, it becomes obvious that the changes were not made by re-engraving the master dies. Such major changes to both obverse and reverse designs could only have been accomplished by the making of two new galvanos.

TYPE II

.Images are courtesy of Heritage Auctions

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- Next Page »