‘Sandwich strikes’ shouldn’t be confused with

‘sandwich jobs’

|

|

|

Machine parts above By Mike Diamond | 05-21-11 As a coin is struck, its expansion When the collar fails to deploy, a On some occasions a coin’s expansion The most familiar obstacle to A typical example is shown here in Sideneck strikes are always concave Strike-related edge damage of In either case, we can’t be sure The introduction of the Schuler The dies evidently struck whatever This type of edge damage can be The affected coins all show a sequence Coin World’s

MD-13Die adjustment strike’ remains a persistent, pertinacious myth

2011 05 30

|

Machine By Mike Diamond | May 21, 2011 | ||||||||||

|

|

An Images by Mike Diamond. |

|

As When On The A Sideneck Strike-related In The The This The Coin |

|

http://www.coinworld.com/articles/machine-parts-above-collar-can-impede-expandi/

Copyright |

By William T. Gibbs Coin

World Staff |

July 01, 2011 1:33 p.m.

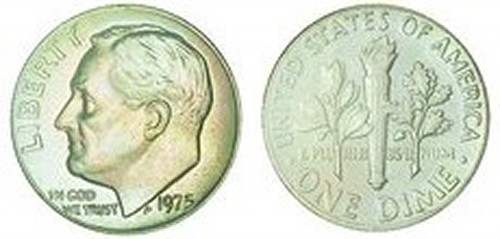

This photograph taken June 27 shows the Proof 1975-S Roosevelt, No S dime that was first reported in July 1977 and out of public sight since. A faint, squiggly struck-through area adjacent to and extending into the top of the torch can also be seen on a photograph of the same piece taken in 1977. The photos were taken through the plastic case of the Proof set. Coin World images.

An Ohio collector who read the June 20 Coin World’s coverage about the consignment of one of the two known examples of the dime to the August American Numismatic Association convention auction by Stack’s Bowers Galleries brought his family’s set to Coin World’s offices as well as documentation supporting their purchase of the set more than three decades ago. The middle-aged man and his octogenarian mother visited Coin World’s offices twice in June, first to share the documentation with staff and to talk about the set, and a second time with the set, which had been safely stored in a lock box.

The family has owned the set for more than 30 years and plans to keep it for decades more.

A June 27 examination of the dime in the set, and in comparison with photographs taken in 1977 and with the images on a 1983 ANACS certificate, confirms that the dime is the same piece Coin World staff — including this author — examined in 1977. The dime has a visible, unique marker not seen in the photographs of the other example. The Ohio coin was struck through a thread or hair on the reverse that left a shallow depression in the coin extending from the field to the right of the top of the torch into the bottom of the flames. The squiggly struck-through area is visible both on the dime and in the Coin World photograph from 1977.

In addition, the dime shows a patch of roughness on the torch visible on the coin, on the 1977 Coin World photograph and on a 1983 ANACS photo certificate. No such roughness is visible on the coin consigned to Stack’s Bowers Galleries.

ANACS, when it was the ANA Certification Service, authenticated the dime as a Proof in the fall of 1977 after getting permission from the owner to open the set for closer visual examination. The ANACS authentication occurred a few months after Coin World staff saw the piece and informed the owner that they could not identify the piece as a Proof, in part because the coin was housed within the Mint packaging, which restricted visual inspection. The Coin World staff noted several imperfections on the coin that are unusual though not impossible on Proof coinage.

Coin World reported on the ANACS authentication of the dime in its Feb. 22, 1978, issue. The same page One article also noted, “One other coin like this has been reported but not verified.” ANACS authenticated the second coin a few months later, which was then reported in the July 5, 1978, issue of Coin World.

The first coin authenticated bears ANACS photo certificate serial No. E-6781-A. The second coin authenticated bears certificate serial number E-3674-B. The suffix letter B indicates that the coin in the upcoming Stack’s Bowers Galleries was authenticated after the coin with the serial number ending in “A.”

About the same time as Coin World reported that the first dime had been authenticated, it entered the marketplace. Within a few weeks of the February publication, the coin was sold to a collector who, by coincidence, lived less than an hour’s drive away from Coin World’s Sidney, Ohio, offices.

For the Ohio collector, an early mail delivery in early 1978, plus his proximity to the dealer offering the Proof set with the coin, gave him an edge over other potential customers for the coin.

Fred J. Vollmer, then a Bloomington, Ill., dealer, acquired the set with the No S dime from the original owner during the first quarter of 1978. Vollmer, in his 1970s advertising appearing in Coin World, was known for offering the 1968, 1970 and 1971 Proof sets with No S error coins. Vollmer, now retired, told Coin World in late June that the seller contacted him after seeing his advertisements for those earlier sets. He said that he conducted the transaction through the mail and never met the seller.

After acquiring the set, Vollmer mailed a letter to clients (apparently a dozen or so individuals) who had purchased from him the earlier Proof sets with error No S coins, clients including to the Ohio collector. The Ohio man told Coin World that he had purchased an example of the 1968-S Proof set with the 1968-S Roosevelt, No S dime from Vollmer in 1976.

The proximity of Voltmeters business to the Ohio collector’s location probably meant the Ohioan received his letter sooner than most of the other customers. More importantly, a fortuitous early mail delivery that day enabled the Ohio collector (who has asked for anonymity) to buy the set.

He told Coin World in June that his postal carrier delivered mail the day he received Vollmer’s letter (in early March 1978) about an hour earlier than normal. Upon opening and reading the letter, the Ohio collector telephoned Vollmer within two or three minutes to say that he wanted to purchase the set. According to the Ohio collector, Vollmer later told him that a second individual wanting the set called him less than 10 minutes later. The Ohio collector indicated that, had his mail been delivered at the normal time that day, he probably would not have been able to purchase the set.

Buying on an installment plan Vollmer and the Ohio collector and his family agreed on a price. According to the March 10, 1978, invoice from Vollmer, which the collector shared with Coin World, the purchase price was $18,200. The collector purchased the coin on a two-year installment plan, paying Vollmer $3,800 as a down payment. Vollmer added $800 to the purchase price as a service fee for the installment plan. The collector paid Vollmer $633.33 monthly, with a final payment of $833.41. The Ohio collector and his family did not take possession of the set with the dime until the final payment was made in 1980. The collector and his family drove from their Ohio location to Vollmer’s shop in Illinois to pick up the set, in completion of the transaction.

Before that conclusion of the transaction, however, Vollmer offered the Ohio collector the second set that had been authenticated as Proof by ANACS. This time, however, the asking price was much higher than the $18,200 Vollmer asked for the first set. And, apparently reported here for the first time, the person who sold Vollmer the first set also sold the dealer the second set. Two sets, one finder Vollmer told Coin World in June that the same California individual found both sets in a box of five acquired from the Mint and sold both to him, though on separate occasions. Vollmer did not recall the name of the seller, although that information is included in Coin World’s files from July 1977. The individual, who sent Coin World the set in 1977, requested anonymity at that time, which was granted and is still being honored.

While the Ohio collector who bought the first set was aware that the same person had found both sets that information does not appear to have been previously published. In a letter dated Feb. 20, 1979, Vollmer wrote to the Ohio collector with the offer of the second set.

“I have enclosed a letter from the customer that we purchased your 1975 NO S PROOF SET [from],” Vollmer wrote in the 1979 letter. “This letter is offering the SECOND KNOWN SET that we found out about, just after we purchased the first set. Little did I know this same person owned the other set. As you know I have spent much time trying to locate the second set, and have NEVER been offered or rumored [sic] of another set until this letter came to me. I have had three 1975 [Uncirculated] mint sets sent to me for the NO S PROOF SET.”

Vollmer continued in the 1979 letter: “We are offering this [second set] to customers that we held a list of when we offered this [first] set last year. However in this offering it will be sold on a first come basis. I think that you can read between the lines that we really had to reach to buy this set, and was not near the nice deal of the first. Our price is $38,550/00 with 10% down, balance on April 1st 1979. We can set it up also on a two year LAY-A-WAY with only 5% added to sale price, 20% down.”

Vollmer noted that customers might think him “MAD” for asking $38,550 for the second set, but he pointed out in the letter that no other sets had surfaced, and, “Remember we are also in a wild coin market with super prices being made weekly, and the dollars are buying less.” In his letter to the Ohio collector, Vollmer said that if the Ohioan would also purchase the second set, Vollmer would work with him if he ever decided to sell both sets, charging him a percentage of the sale price. Vollmer concluded the letter with a prediction that a six-figure set would be “at this point well within reach.”

The Ohio collector called Vollmer about the second set but found that it had already been sold. In any case, he was reluctant to purchase the second set because of the higher price. Another buyer had purchased the second set, on an installment plan. When the Ohio collector picked up his set in 1980, Vollmer showed him the other set, which he still held for its purchaser. According to the Ohio collector, Vollmer believed that the first dime was of higher quality than the second. (Professional Coin Grading Service recently graded that second coin, offered in the upcoming Stack’s Bowers auction, as Proof 68.) Erroneous assumption.

When the first two news accounts about the sets were published in Coin World in February and July 1978, Coin World staff did not know that the same collector had found both sets. Coin World did report in the July 5, 1978, issue that both sets had been found in California, according to ANACS staff and Coin World’s records for the first set. ANACS also maintained the anonymity of the finder of the second set, despite the close working relationship between ANACS and Collectors’ Clearinghouse staff at the time. ANACS’s chief authenticator in 1978 was Edward Fleischmann, who had been editor of Coin World’s Collectors’ Clearinghouse department in the early 1970-s. Fleischmann left Coin World for ANACS in 1976 and was replaced in the Coin World position by his assistant, Thomas K. DeLorey. (DeLorey’s elevation to editorship of the Clearinghouse column opened a position on the staff for the current writer, which was filled in October 1976.)

DeLorey said June 30: “To the best of my recollection Ed never said anything about who owned the second piece. I am fairly certain that I just assumed it was from another party, but I have no recollection of making that assumption. It is just that if I had known that the same party had ‘found’ both pieces, that is the kind of thing I would have remembered.” Because Coin World was unaware that the same person had found both sets, an incorrect conclusion was presented in our coverage in the June 20 issue: that the coin consigned to Stack’s Bowers Galleries was from the set sent to Coin World for examination in 1977. When Stack’s Bowers Galleries first contacted Coin World about the consignment of the dime, a spokeswoman for the firm gave Coin World the name of the original owner. Since that name matched the name in Coin World records from 1977, the logical, though erroneous, assumption was made that the coin to be auctioned was the one reported in 1977.

Coin World has since attempted to locate and contact the original owner of the sets. A message was left on a telephone answering machine at a number linked to a person that Internet searches tie to the name and address given in the 1977 correspondence in files. As of June 30, no one at that number had returned Coin World’s call.

Why so rare?

While none of the Proof sets with error No S coins are common (estimated mintages for the 1968, 1970, 1971, 1983 and 1990 sets all range in the few thousands), the 1975 Proof set with the No S dime is by far the rarest. Just two sets have ever been authenticated, and until the two sets surfaced recently, they had not been seen in the marketplace for decades. That both sets were found by the same person, reportedly in a purchase from the Mint, could be considered remarkable. In consideration of that single finder’s address and the historical record, some additional questions are raised.

The 1977 home of the original finder was in a community a short distance south of San Francisco, location of the San Francisco Assay Office, source of the set (which has since gained Mint status). That proximity could easily be mere coincidence, of course. However, it is also a matter of historical record that during the early to mid-1970s, a group of San Francisco Assay Office employees clandestinely struck Proof “error” coins. These coins were of the striking and planchet error categories, most of them so deformed that they would never have fit into the hard plastic case used for Proof sets in the late 1960s and 1970s. The Proof errors that were clandestinely struck were not of the die variety category (under which the No S dime is classified). The illicit error coins were smuggled out of the facility in the oil pans of forklifts, into which they had been dropped through the oil filler spout. When the forklifts were sent outside the Mint facility for servicing, confederates of the assay office employees retrieved the “error” coins, which, after the oil coating them was removed with gasoline, were then sold into the marketplace. Coin dealers became suspicious of the types and quantities of Proof error coins entering the marketplace. Eventually, some collectors who knew how the coins were smuggled out of the Mint let the secret out. Several reputable coin dealers then contacted Bureau of the Mint officials. The ensuing investigation uncovered the conspiracy, and officials shut down the clandestine minting operation. The supply of Proof errors from the facility dried up about 1976 and 1977, according to error specialists active in the 1970s. It is entirely possible, maybe even likely, that the Proof 1975-S Roosevelt, No S dimes were made legitimately. After all, similar die varieties had already been made in 1968, 1970 and 1971, and would again be made in 1983 and 1990, all of which were released through regular Mint channels to collectors who ordered sets from the Mint, and the No S coins were unlike the error coins being made clandestinely. However, the rarity of the 1975 sets could possibly be attributed to the investigation into the clandestine operations at the San Francisco Assay Office. If the sets had been made in larger quantities but, under the increased scrutiny, were discovered by Mint officials, it is possible that most of the sets were caught before they could be released.

The rarity of the Proof 1975 set with the No S dime makes it the key of the small series of Proof error coins lacking the Mint mark. Neither of the two coins has ever been offered at auction, and the transactions have been few. When the coin consigned to Stack’s Bowers Galleries is offered at auction in Rosemont, Ill., in August during the ANA convention auction, the sale will be the first time either of the sets has been offered in decades.

The Ohio collector has kept his family’s ownership a closely held secret for decades. He noted, however, that at the ANA convention in Cincinnati in 1980, he was standing talking with a prominent dealer when a third party stepped up to join them in the conversation. The third party then asked whether they thought the 1975 Proof set with the No S dime would be on exhibit at the convention. The Ohio owner of the set chose not to reveal his ownership. As for the Ohio collector’s set, he told Coin World June 28 that the family’s set would not be made available in the marketplace for decades, which would seem to ensure that the coin consigned to the August Stack’s Bowers Galleries auction might be the only piece available to collectors for a long time to come. ?

http://www.coinworld.com/articles/both-known-proof-1975-no-s-dimes-surface/

Copyright

2012 by Amos Hobby Publishing Inc. Reposted by permission from the March 22,

2012, issue of Coin World.)

Article first published in 2011-08-01, U.S. Collectibles section

A California collector’s “Frosted Freedom” Proof 2007-W American Eagle platinum $50 coin has been authenticated by Numismatic Guaranty Corp. and given a grade of Proof 69 Ultra Cameo. It is the first $50 platinum coin, and the third overall piece, confirmed as bearing this variant surface detail.

Image courtesy of owner

The owner of the coin, a California collector who wishes to remain anonymous, discovered the anomalous coin in a four-piece set that he purchased directly from the U.S. Mint in 2007.

All of the Frosted Freedom coins are “pre-production” strikes inadvertently released by the United States Mint. The pre-production and regular production pieces are distinguished by the surface treatment of the word freedom on the reverse. The word is frosted on the pre-production pieces and mirrored on production strikes.

Several months after reading Coin World’s reporting of the variant, the collector retrieved his sets from storage and made the discovery. He then submitted the coin to be authenticated and graded by NGC.

Previous Proof 2007-W American Eagle platinum coins discovered bearing the Frosted Freedom reverse are a 1-ounce $100 piece and a quarter-ounce $25 coin. The recently discovered $50 coin is the first of its denomination found bearing this variety and has been labeled by NGC as a “Discovery Specimen.”

NGC has graded the piece Proof 69 Ultra Cameo.

The discovery of the first Frosted Freedom variety coin was originally reported in the Feb. 7, 2011, issue of Coin World, when NGC announced it had certified a 1-ounce $100 piece as a new variety.

Graded by NGC as Proof 70 ultra cameo, the 2007-W 1-ounce coin was labeled as “FROSTED FREEDOM” and “DISCOVERY SPECIMEN” on its encapsulation label.

Details of design differences:

The reverse of all Proof 2007-W American Eagle platinum coins features an eagle with outstretched wings with a shield covering the eagle’s breast. Draped over this shield is a banner inscribed with the W Mint mark of the West Point Mint at left (as seen from the perspective of the viewer) and the word freedom at right.

On 2007-W platinum coins having a normal polishing pattern, the incused word freedom displays the same brilliant finish as the coin’s fields, thus standing out sharply within the frosted banner.

The variant coins, however, have the legend freedom frosted, so that it blends in with the rest of the design on the reverse.

Though not error coins, their sale to the public was an error on the part of the U. S. Mint.

The Mint confirmed that a small number of the coins were struck as “pre-production” pieces and inadvertently released for sale. Michael White of the Mint’s Office of Public Affairs stated that during the pre-production process, officials decided that the word freedom on the reverse would look better with a mirror finish than frosted as originally designed, and prepared new dies for regular production.

According to the Mint, up to 12 1-ounce coins, 21 half-ounce coins and 21 quarter-ounce coins with the frosted freedom inscription were mistakenly sold. The Mint reported it struck no tenth-ounce $10 platinum strikes bearing the frosted finish for the word freedom.

Overall, the Mint sold 8,176 tenth-ounce pieces, 6,017 quarter-ounce pieces, 22,873 half-ounce pieces and 8,363 1-ounce pieces in the Proof 2007-W American Eagle platinum coin program.

The owner of the $50 variant piece tells Coin World that he has no plans to sell the coin. ?

http://www.coinworld.com/articles/third-2007-w-frosted-freedom-platinum-ae-coin/

Copyright 2012 by Amos Hobby Publishing Inc. Reposted by permission from the March 22, 2012, issue of Coin World.)

|

Clarity of incuse ghost images dependent on coin thickness By Mike Diamond-Special to Coin World | July 23, 2011 10:00 a.m. Article first published in 2011-08-01, Expert Advice section of Coin World

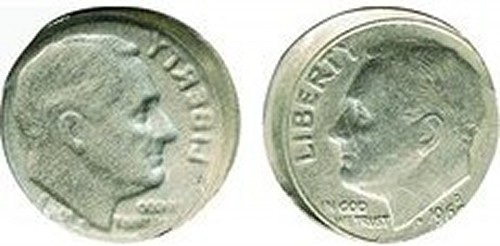

This slightly off-center Roosevelt dime clad layer carries a clear incuse ghost image of the obverse design on its reverse face. Images by Mike Diamond. |

|

|

Flash any error collector an image of an extensive, incuse mirror-image and the first candidate explanation that comes to mind is a brockage. A brockage is formed when a coin (or any piece of die-struck, hard material) is driven into a planchet or another coin. However, the incuse mirror-image on the reverse face of the illustrated 1969-D Roosevelt dime is not a brockage. It is instead an incuse ghost image. This is a copper-nickel clad layer that either separated from an off-center dime after the strike or that entered the striking chamber on top of a normal dime planchet. While these two possibilities cannot be disentangled, the effect on this exceedingly thin and lightweight (0.37 gram) disc is the same. The side of the disc that was in direct contact with the obverse die molded itself to the recesses of the die face. The side that was in contact with the underlying planchet (or that was loosely adherent to the copper core) also sank into the recesses of the obverse die. Any thin disc that enters the striking chamber together with another planchet will obey the same principle. This is illustrated here by an undated Lincoln cent that started out as a split-before-strike planchet. Weighing 1.54 grams, it was inserted into the striking chamber beneath another planchet. The resulting in-collar uniface strike (full indent) left the coin with an incuse ghost image of the Lincoln Memorial on the obverse face. A similar-looking incuse Lincoln Memorial formed under somewhat different circumstances in the double-struck 1977 Lincoln cent presented here. This 1.58-gram example entered the striking chamber as a rolled-thin or split-before-strike planchet. The first strike left it with a die-struck design on both faces but no ghost image. The second strike took place beneath a planchet. This flattened the die-struck obverse design and generated the incuse ghost Lincoln Memorial. A coin that is thinned by multiple strikes against a succession of planchets will gradually develop a clear incuse ghost image. That’s what happened to the multi-struck 1996 Lincoln cent shown here. Weighing only 0.24 gram, its reverse face shows a mirror image of the obverse design. This demi-coin is the detached bottom of a late-stage obverse (hammer) die cap. The copper plating was completely worn away as the cap’s working face struck a series of planchets. Detached cap bottoms are often mistakenly assigned to an error type that doesn’t even exist among copper-plated zinc cents — the “split-after-strike shell.” A planchet or coin of normal thickness can also develop an incuse ghost image if it receives an unusually strong off-center uniface strike that reduces its final thickness to a fraction of its original girth. Illustrating this phenomenon is a double-struck 1998 cent in which the second strike was 60 percent off-center, with the obverse face covered by a planchet. A strong incuse ghost image of the Lincoln Memorial has formed on the obverse face. Distinguishing an incuse ghost image from a brockage is usually not too difficult. Most brockages show at least some expansion, while a ghost image is never expanded. Fine details are muted or lost in a ghost image, while they’re usually clear in an unexpanded, first-strike brockage. In a ghost image, it is often the centrally located, highest-relief portions of the design that are easiest to recognize (they may, in fact, be the only recognizable elements). The final factor to be considered is thickness. The thinner the metal, the clearer the ghost image. Usually the opposite is true of brockages. A planchet or coin thinned by the strike will generally show an expanded and distorted brockage. Coin World’s Collectors’ Clearinghouse department does not accept coins or other items for examination without prior permission from News Editor William T. Gibbs. Materials sent to Clearinghouse without prior permission will be returned unexamined. Please address all Clearinghouse inquiries tocweditor@coinworld.com or to (800)

|

|

http://www.coinworld.com/articles/clarity-of-incuse-ghost-images-dependent-on-c/ Copyright

|

|

By Paul Gilkes-Coin World Staff | July 20, 2011 10:00 a.m.

California collector Lee Lydston obtained at face value at a local bank this wrong planchet error 1973-S Eisenhower dollar struck on a copper-nickel clad planchet instead of the intended silver-copper clad planchet. Images by Todd Pollack of BlueCC Photo, |

|

An Eisenhower dollar recently obtained at face value from a California bank has been authenticated as a 1973-S dollar struck on a copper-nickel clad planchet instead of the intended silver-copper clad planchet.

Collector Lee Lydston submitted the coin to Numismatic Guaranty Corp., which certified the coin as a wrong planchet error and graded it About Uncirculated 58.

Lydston’s coin is only the second such wrong planchet error involving a 1973-S Eisenhower dollar that NGC has certified.

The discovery piece, which NGC graded Mint State 67, was obtained in September 2008 by John Wrublewski from Pioneer Numismatics in Acton, Mass. Wrublewski’s Uncirculated coin was housed in its original “Blue Ike” packaging from the U.S. Mint, and was contained in a coin lot he purchased for $150 at auction. Wrublewski’s coin, which he figured cost him $6, has been subsequently valued in the five figures.

Both Lydston’s and Wrublewski’s coins were struck on copper-nickel clad planchets (outer layers of 75 percent copper, 25 percent nickel, bonded to a core of pure copper), of the kind used for circulation strikes. The coin should have been struck on a silver-copper planchet (80 percent silver, 20 percent copper, bonded to a core of 21.5 percent silver 78.5 percent copper), the sole composition used for collector Uncirculated and Proof versions in 1973.

The weights of both error coins are near the standard 22.68-gram weight of the copper-nickel clad coins instead of the 24.59-gram weight for the silver planchets.

The edges of both Lydston’s and Wrublewski’s coins exhibit the exposed copper core, instead of the silver edge of the silver coins.

Bank find

Lydston said he was returning a $1,000 face value bag of Kennedy half dollars to the bank when he asked a teller if she had any unusual coins for him to examined. Lydston said the teller handed him three Eisenhower dollars – one was a 1971-D dollar, one a 1972 coin and the third a 1973-S coin.

Lydston said he looked at the first two coins looking for the rare Type 2 reverses on both coins, but both were Type 1s. “I wasn’t that impressed with finding a 1973 in circulation even though these were ‘mint set only’ coins and I’ve gotten them really cheaply in a raw state from local coin dealers but this one, looked fairly clean for a circulated coin,” Lydston said. “Almost with a satiny finish. I figured, what the heck, and plunked down my buck for the coin.”

Lydston said copper-nickel clad dollars typically have “a fair amount of Mint luster or shine, if you will, even when circulated. This coin was not particularly lustrous and had more of a clean, satiny finish, which is what caught my eye.”

He said “making the decision to ‘drag yet another Ike home’ was based more upon the appearance of the coin coupled with its date than simply the date of the coin.”

Since Lydston did not have a source of magnification at the bank, he had not checked the coin for a Mint mark. Lydston said when he returned home from the bank, he examined the coin under magnification and found the S Mint mark, and further checked the edge to see the exposed copper core.

“Being sensitive to the prolific counterfeiters out of China, I then took it to the scope for a close up look at the finish,” said Lydston, who specializes in Eisenhower dollars. “The coin definitely had the crisp quality of a U.S. Mint product and certain die markers from 40 percent silver 1973-S Ike’s were quite evident on the reverse eagle’s breast.

“The surfaces showed wear from circulation contact, but the protected area’s near the devices were satiny smooth.” ?

|

|

|

http://www.coinworld.com/articles/1973-s-dollar-struck-on-circulation-planchet/

Copyright

|

Article first published in 2011-08-11, New Finds section of Coin World.

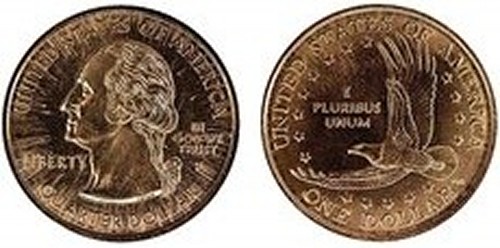

NGC graded this most recently reported Sacagawea dollar/Washington quarter dollar error, now the 11th known example, as Mint State 67. It was struck from Die Pair 1. The close-up image shows the diagnostic die crack on the reverse, on the f in of.

Images courtesy of Numismatic Guaranty Corp.

An 11th example of the undated double-denominated Sacagawea dollar/Washington quarter dollar mule error coin has surfaced, 11 years after the first example was found in Arkansas in 2000.

Nicholas P. Brown, owner of Majestic Rarities in Chicago, confirmed to Coin World July 12 his purchase of the coin from its owner, who wishes to remain anonymous. Brown would not disclose the purchase price, and added he had

not yet physically seen the coin.

The coin was submitted to Numismatic Guaranty Corp., which authenticated the coin as an example of the double-denomination mule error and graded it Mint State 67, according to David J. Camire, president of Numismatic Conservation Services, a sister company to NGC for whom he is also the error coin specialist. Camire said the current example is tied for the finest known specimen among the 11 confirmed pieces.

A mule is a coin, token or medal struck with dies not intended to be paired together. What makes the production of this mule error more unusual is that a State quarter dollar obverse die was paired with a Sacagawea dollar reverse die not once, but three times. The known mules are known to have been struck with three separate and distinct die pairs mounted in a coinage press dedicated to the production of dollar coins.

Camire said Brown’s coin was struck from Die Pair 1. The key diagnostic is the reverse for Die Pair 1 exhibits a die crack in the f in of in united states of america that is absent from the reverses from Die Pairs 2 and 3. Complete diagnostics for all three die pairs appear later in this article. Of the now 11 publicly known examples, six are from Die Pair 1, three from Die Pair 2 and two from Die Pair 3. Eleventh example Brown said July 13 that he was one of several persons approached by the unnamed seller about buying the coin, a process that began three weeks before the deal was completed. Brown said once he learned he was the top bidder, he had the seller send the coin directly to NGC for authentication and certification before the transaction would be completed. The transaction was completed, Brown said, after he received confirmation from NGC that the mule had indeed been authenticated as genuine, graded and encapsulated.

Brown would not disclose the specific location of the seller, other than to say the coin came from the East Coast. He said the seller acquired the coin through purchase and held onto it for the past 10 to 10 and a half years. Brown said the individual who sold the coin to him did not learn from the person from whom it was originally purchased how the coin was discovered — whether in change, from a roll or bag of coins, or purchased from someone else.

Brown does not plan to sell the coin at this time, but will have it on display at his table Aug. 16 to 20 at the American Numismatic Association World’s Fair of Money in Rosemont, Ill.

The book 100 Greatest U.S. Error Coins, co-authored by Brown, Camire and California coin dealer and error coin specialist Fred Weinberg, recognizes the quarter dollar/dollar mule as the No. 1 U.S. coin error. The authors suggest that approximately 13 examples are known, but the reference published in 2010 pedigrees 10 publicly known pieces.

Discovery

For error coin collectors, Sacagawea dollars and State quarter dollars offered hobbyists two new series to search through in 2000 in the hopes of finding something valuable. Until May of that year, however, no one suspected that an error would be found that combined designs from both coins.

In June 2000, Numismatic Guaranty Corp. announced that it had authenticated a coin bearing the obverse of a State quarter dollar and the reverse of a Sacagawea dollar, struck on a dollar planchet. The mixture of designs struck by

dies for two different denominations was the first error of its kind confirmed on a U.S. coin in the 208-year history of the U.S. Mint — a type of error called a mule by specialists.

U.S. Mint officials confirmed the mule error in a statement released Aug. 4, 2000.

The quarter dollar/dollar mules discovered in 2000 are undated and bear the P Mint mark for the Philadelphia Mint. The reverse die for State quarter dollars (not used for the mule) bears the date along the top border, the same side as

the design representing the respective state. The date appears on the obverse die for the 2000 to 2008 Sacagawea dollars (also not used).

The first example of the mule was discovered by Frank Wallis in late May 2000 in an Uncirculated 25-coin roll of Sacagawea dollars obtained from First National Bank & Trust in Mountain Home, Ark. The area is part of the St. Louis Federal Reserve District.

NGC graded the Wallis coin Mint State 66, but a month later the coin was crossed over to a Professional Coin Grading Service encapsulation. PCGS also graded the coin MS-66.

Since the original find, grading services have authenticated, in all, 11 examples of the mule. Nine of the coins have been sold, either in private transactions or at auction, at published prices reaching as high as $70,000. Brown notes that the authors of the 100 Greatest book have confirmation of two pieces changing hands for in excess of $200,000. One coin remains the property of the man who found it.

Mint investigation

U.S. Mint officials determined the mules were struck sometime in late April or early May 2000. Coin World sources in 2000 indicated that the Mint may have produced as many as three bins of the coins, although the sources could not tell Coin World what size bins were involved. If the larger of two different bins in typical use at the Mint were involved, the number of mules struck could have totaled several hundred thousand pieces.

When Mint officials discovered the error, they impounded several bins — one that may have contained tens of thousands of the mule errors struck by one press, as well as the bins from two other adjoining coining presses. The coins were ordered destroyed.

Production of the mules led to an intensive investigation by Treasury and Mint authorities. The investigation led authorities to a Federal Reserve-contracted coin terminal and wrapping facility located near the Philadelphia Mint, and authorities advised officials there to be on the lookout for any of the mule errors. An undisclosed number of mules were found at the facility.

While a government investigation found that the errors were produced by mistake and not deliberately, two former Philadelphia Mint coin press operators were prosecuted on charges of selling, but not stealing, up to five of the mules and converting the profits to their own use.

U.S. Mint officials in the summer of 2002 indicated the possibility they might seek forfeiture of some of the double-denomination errors depending on when they were discovered and whether they may have left the Philadelphia Mint

illegally, but to this date officials have not pursued civil forfeiture proceedings.

Three die pairs

Hobby experts by the fall of 2000 had determined that multiple die pairs existed for the coin, which might suggest large numbers of the errors were struck. Government investigators were slow to accept the findings of numismatists that multiple die pairs were used in making the coins; investigators did not accept the findings of numismatists until September 2001.

Here’s how to distinguish the three die pairs:

??Die Pair 1: The reverse for Die Pair 1 exhibits a die crack in the f in of in united states of america that is absent from the reverses from Die Pairs 2 and 3. The obverse exhibits numerous radial striations attributable to stresses involved during striking, resulting from the slight differences in size between the two dies. The discovery coin is from Die Pair 1.

??Die Pair 2: Die Pair 2 exhibits a perfect obverse die, but a reverse that shows three noticeable die cracks: one each projecting from the rightmost points of the stars above the e of one and d of dollar and a third, curved die crack running along the wing directly above these two letters.

??Die Pair 3: For Die Pair 3, the obverse has been described as “fresh and frosty.” The obverse of the Die Pair 3 coins shows just a hint of the radial lines found on the discovery example. A small die gouge appears in front of Washington’s lips. The reverse appears perfect and exhibits no die cracks.

Replicas exist

In addition to the genuine mules, collectors should be aware that altered coins/replicas resembling the mules are also in the market. The pieces are made by several novelty companies and produced by machining out the obverse of a genuine Sacagawea dollar, and then inserting and gluing in a machined-down State quarter dollar with its Washington obverse facing out. The altered piece is then plated over to simulate the color of the Sacagawea dollar.

To identify the replica, look for a seam where the field meets the rim. The altered piece’s weight will be off from the 8.1 grams of a genuine Sacagawea dollar, and the altered piece will produce a thud instead of a distinct ring when tapped, a result of its method of assemblage.

Additional mules surface

Since the discovery of the 2000 mule, several earlier U.S. mules have surfaced and been authenticated: from a 1995-D Lincoln cent obverse die and Roosevelt dime reverse die, struck on a cent planchet; from a 1995 Lincoln cent obverse die and Roosevelt dime reverse die, produced on a dime planchet; and a coin produced from a 1999 cent obverse die and dime reverse die, struck on a cent planchet.

http://www.coinworld.com/articles/11th-quarter-dollar-dollar-mule-surfaces/

Copyright 2012 by Amos Hobby Publishing Inc. Reposted by permission from the March 22, 2012, issue of Coin World.)

|

2011-11-14

|