Inverted Die Installation (and how to recognize it)

by Mike Diamond

Throughout most of the U.S. Mint’s history, coins were struck by dies that were set up so that the obverse die functioned as the hammer die and the reverse die functioned as the anvil die. The hammer die delivers the blow, while the anvil die receives the blow, with the planchet sandwiched in between. It is no longer safe to assume that the hammer die is the “top” die and the anvil die is the “bottom” die. Some of the newer presses reportedly operate with the dies oriented horizontally, and Alan Herbert tells me that at least one model of Graebner press first produced in the 1970’s employed a hammer die that thrust upward. At various points in the Mint’s history, the usual pattern of installation was inverted, so that the reverse die functioned as the hammer die and the obverse die functioned as the anvil die (Pilliod, 2000). Buffalo nickels and Mercury dimes were the last 20th century issues to be struck exclusively with inverted dies. It’s not clear why inverted installation was chosen for these and other obsolete issues. After 1945 (the last year in which Mercury dimes were produced), the mint returned to its usual habit of striking coins with a standard die installation (obverse die as hammer die). At least that was the case until the last decade of the 20th century. The status quo was interrupted when Arnold Margolis (1997a, b) reported the discovery of a 1992-D quarter with a reversed partial collar error – a clear indicator of inverted die installation. This was confirmed by personnel of the U.S. Mint after Margolis submitted the coin for examination.

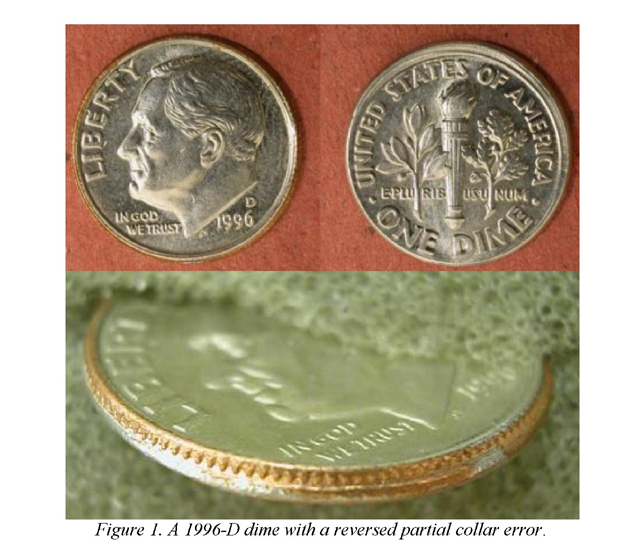

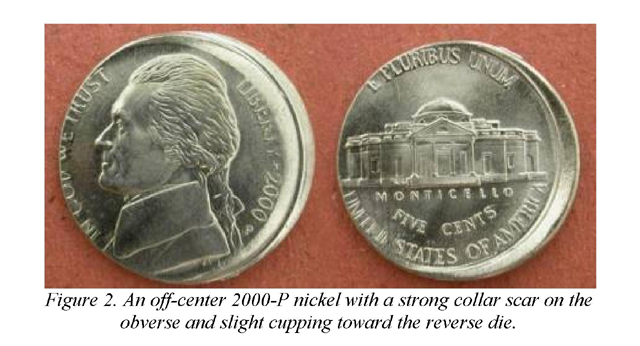

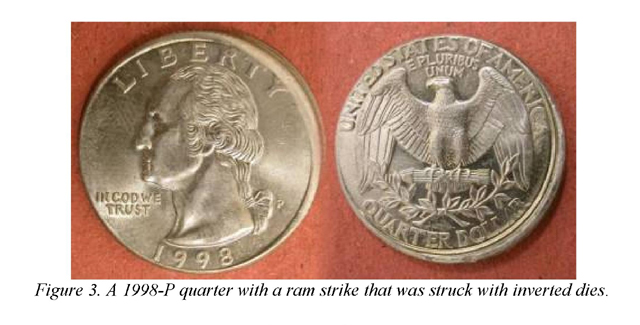

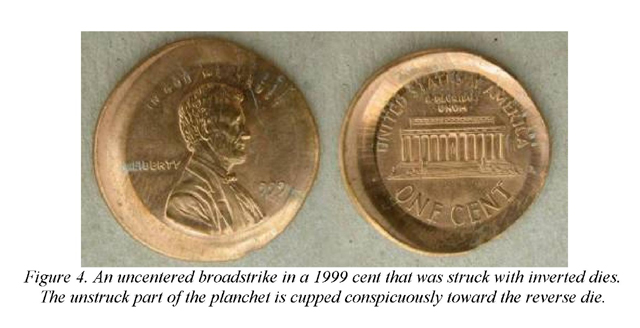

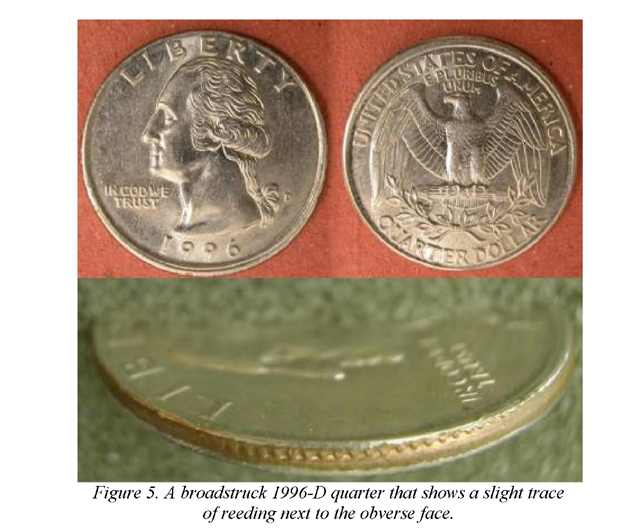

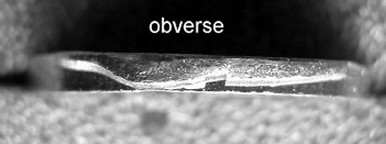

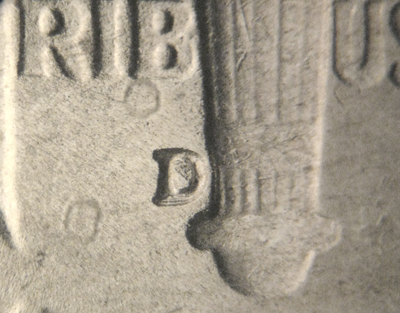

A partial collar error occurs when the collar (the retaining ring that establishes the final diameter of the coin) is not fully deployed during the strike. As a result, part of the coin protrudes above the collar, and it consequently expands beyond its normal diameter in this area. The edge will show a protruding “step” or “flange” that extends out from the face that was positioned above the level of the collar. This face is the one struck by the hammer die, since the collar always surrounds the neck of the anvil die. In coins with reeded edges, the smooth-edged flange will be associated with the face struck by the hammer die, while the thin band of reeding below it will be associated with the face struck by the anvil die. So far, this 1992-D quarter is the only error coin from that year that shows evidence of inverted die installation. It must be understood that it is impossible to determine which die functioned as the hammer die in a normal coin. The presence of inverted dies is only revealed when it is accompanied by certain kinds of errors. It must also be appreciated that inverted die installation itself is not an error, just an alternative setup that is fully intentional. I am not aware of any error coins from 1993 or 1995 that show evidence of inverted dies. I have one 1994-D dime with a reversed partial collar, so this tells us that the practice may have persisted throughout this period, albeit at a nearly undetectable level. In 1996, the practice of striking coins with inverted dies accelerated. A small number of nickels and dimes with inverted partial collars are known from this year, along with a 1996-D broadstruck quarter with a faint trace of reeding next to the obverse face (see below). All these early examples are from the Denver Mint. By 1997, error coins struck by inverted dies can be found in all denominations from cents to quarters, although they are still quite scarce. 1998 shows a conspicuous increase in the number of error coins struck with inverted dies, and the frequency of such coins seems to grow in each subsequent year. Since 2000, it appears that nearly all state quarters have been struck with inverted dies. Other denominations continue to be struck with both normal and inverted die setups, although today the inverted setup may actually dominate. It is unclear why the minted started tinkering with inverted die installation in 1992, why it remained so uncommon for the next three or four years, and why its frequency has increased steadily since 1998. It does appear that inverted die installation has some connection with some of the newer-style presses, (e.g., Schuler and Graebner), that have been installed in recent years.

Recognizing Inverted Dies

Only certain types of errors will betray the presence of inverted dies. Below is a list of errors that supply reliable clues about die installation.

|

Partial

|