PART V. Planchet Errors

Blanking and Cutting Errors:

Ragged clips:

Definition: A coin with a ragged clip has its circular outline interrupted by a very irregular edge. Ragged clips are traditionally thought to be derived from the unfinished leading or trailing end of the coin metal strip. While these ends are supposed to be trimmed, this step can be accidentally (or intentionally) skipped.

While ragged clips are sometimes referred to as “end of sheet” or “end of strip” clips, this same area is also a likely source for straight clips (see Straight Clip). Therefore the term “ragged clip” is preferred.

Ragged clips can also be derived from the middle of the strip. As the strip is rolled out, ragged fissures sometimes develop. If a blanking die slices through such a fissure, the resulting blank will have a ragged clip indistinguishable from one derived from the ends of the strip.

The shape of a ragged clip is highly variable. Many are straight, some form “ragged notches” and some turn into “ragged fissures”.

The edge texture of a ragged clip is invariably rough and shows some graininess

Ragged clips are sometimes confused with broken coin and broken planchet errors.

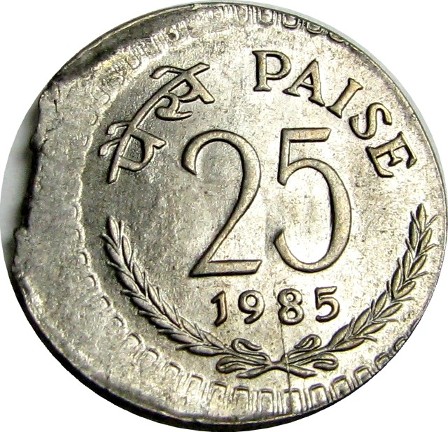

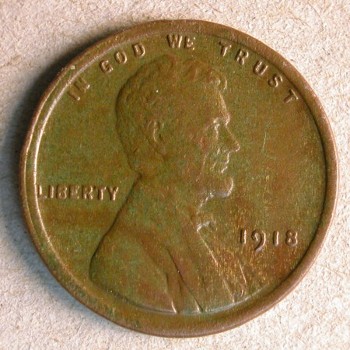

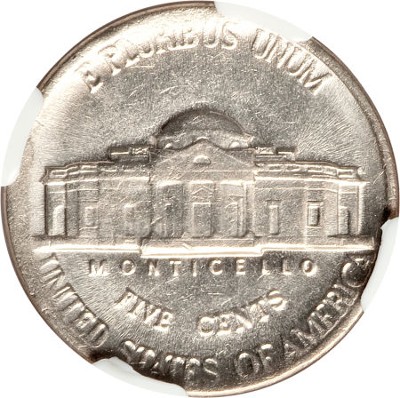

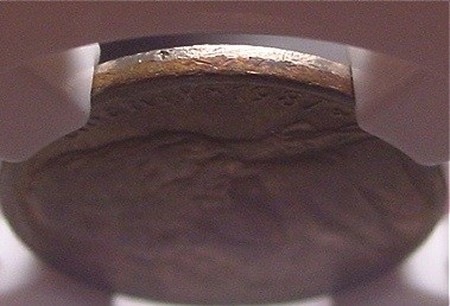

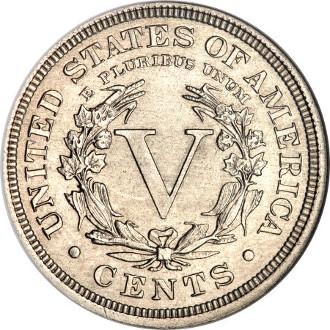

The three images below are a 1985 Indian 25 paise struck off-center with a ragged clip planchet. The lower image isan oblique angle of the grainy edge of the ragged clip.