Machine

parts above collar can impede expanding coins

By Mike Diamond | May 21, 2011

10:00 a.m.

Article

first published in 2011-05-30, Expert Advice section of Coin World

|

An Images by Mike Diamond. |

|

As When On The A Sideneck Strike-related In The The This The Coin |

|

http://www.coinworld.com/articles/machine-parts-above-collar-can-impede-expandi/

Copyright |

2011 12 26

|

2011-12-26

2012 03 19‘Two-tailed’ Canadian cents: mules or pseudo-mules?By Mike Diamond-Special to Coin World |

|

|

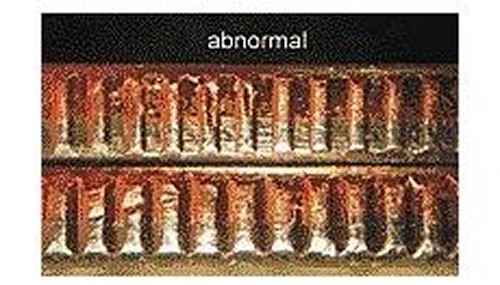

A second case of abnormal reeding on a State quarter dollar By Mike Diamond-Special Article first published in 2012-04-16, Expert Advice section of Coin World

A side-by-side comparison of two 2008-P New Images by Mike Diamond.

|

|

|

A wise old aphorism from the realm of science declares that “fortune favors the prepared mind.” Marilyn Keeney’s mind was certainly prepared when she stumbled across a second example of abnormal reeding in a State quarter dollar. The first example — also discovered by Keeney — was reported in the Jan. 25, 2010, Collectors’ Clearinghouse. Back then she encountered a group of 2008-P New Mexico quarter dollars struck within a single damaged collar. As shown in the accompanying photo, the reeds (vertical ridges) on the edge of each affected coin are unusually low and narrow and are separated from each other by abnormally wide, flat valleys. This appearance reflects damage to the sharp tips of the corresponding ridges on the working face of the collar. The apex of each ridge was removed by abrasion or machining. Horizontal scratches in the valley floors seem to point to the use of some kind of rotating, cylindrical device. The original discussion also included a much earlier case involving a 1964-D Washington quarter dollar. That example showed a similar, but somewhat less uniform pattern of low, narrow reeds and broad, flat valleys. The same sort of collar damage has now been found on the edge of some 2007-P Wyoming quarter dollars. Here the damage is not nearly as severe as that seen in the earlier examples. The damage also affects only about half the edge. The edge exhibits a gradual transition from normal reeding to abnormal reeding, with the widest valleys seen at around 8:00 (obverse clock position). At least three die pairs are represented within a group of five quarter dollars that were found by Keeney. This is not particularly surprising, as the same collar is often used through several die changes. Keeney’s two finds leave little doubt that many other cases of similar damage are yet to be discovered. In fact, I stumbled across another example while rummaging through my modest collection of coins with odd-looking reeding. This time the collar damage was detected on a 1967 quarter dollar that combines a tilted partial collar with an uncentered broadstrike. In other words, the collar was strongly tilted and a portion of it was positioned beneath the plane of the anvil (reverse) die face. The reeds are low, narrow and widely spaced (see photos). A particularly interesting feature is seen at 2:30. Here the reeds taper strongly as they approach the top of the collar. The same phenomenon is seen on the 1964-D Washington quarter dollar. This provides a clue as to the likely cause of the damage in all these examples. In many collars the entrance is beveled. Judging from a large sample of partial collar errors, the length of this beveled transition zone between the top of the collar and its working face is highly variable. A sloping entrance deflects the impact of a misaligned hammer die, helping to prevent damage to both the die and the working face of the collar. It also probably makes for more reliable insertion of the planchet. In either case, the damage would be expected to occur most frequently, and achieve its greatest severity, along the upper portion of the collar’s working face. This neatly explains why the reeds sometimes taper toward the obverse face and the top of the collar. Coin

|

|

http://www.coinworld.com/articles/a-second-case-of-abnormal-reeding-on-a-state-/ Copyright |

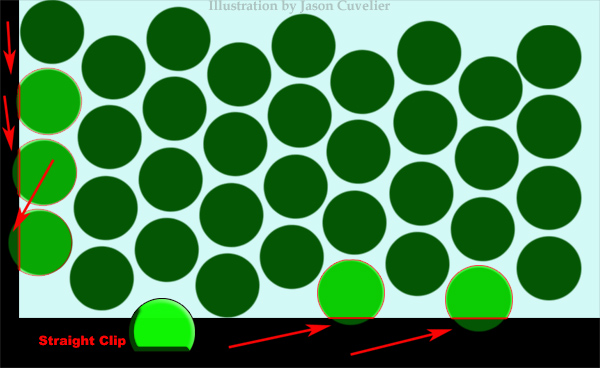

Straight Clips

Part V. Planchet Errors:

Blanking and Cutting Errors:

Straight clips

Definition: A straight clip is thought to result when a blanking die (punch) slices through the leading or trailing end of the coin metal strip. This pre-supposes that the ends were trimmed prior to the coil being fed into the blanking press.

Another possibility is the blanking die slicing through one side of a strip that is too narrow. This situation might arise if the splitter, which divides the original wide strip into narrower slips, is not positioned right in the middle of the coil.

A small percentage of straight clips mark the termination of a planchet taper. This may be where the rollers squeezed the leading or trailing end of the strip down to an abnormally thin gauge.

The edge texture of a straight clip is highly variable. It can be smooth, rough, irregular, or serrated in some fashion. This probably reflects a variety of machines employed for the task — shears, saws, guillotines are three possibilities.

A straight clip appears on a coin as a straight edge. Not all straight edges are straight clips, however. They are sometimes confused with chain strikes, broken planchet and broken coin errors, and various forms of pre-strike damage. When a straight-clipped planchet is struck out of collar, the straight edge often bows out due to the pressure of the strike and attendant expansion of the coin. These secondarily convex straight clips have been mistaken for elliptical clips.

For expanded treatment concerning clip diagnostics click here.

|